Fighting for 403(b) Funds

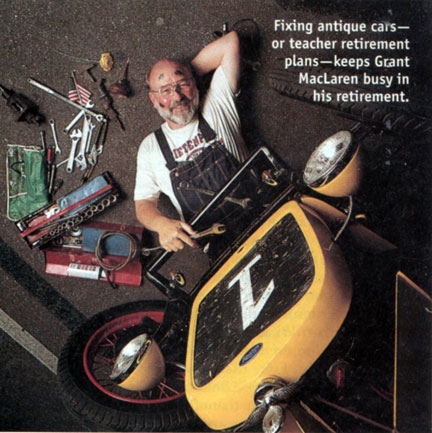

JERRY MAGUIRE, MEET GRANT MACLAREN. LONG BEFORE TOM CRUISE INJECTED “SHOW ME THE MONEY!” INTO THE NATION’S VOCABULARY, MACLAREN WAS ADDICTED TO A SIMILAR slogan: “Show me the mutual funds!” MacLaren, a retired community college administrator in St. Louis, wants to see no-load funds on the menu of 403(b) tax-deferred retirement plans offered to public school teachers. That might not seem like a lot to ask, considering the giddy love affair that investors have been carrying on with funds. But MacLaren has run into stubborn opposition. He’s had to persuade school administrators that his proposal is legal—it is—and then drum up support to get it implemented. The problem is that 403(b) plans—which, like 401(k) plans offered by for-profit employers, let workers accumulate pretax earnings—are also known as tax-sheltered annuities. Not surprisingly, a lot of people think that something called an annuity has to be an annuity—an investment sold by insurance companies. And that’s the way it was when 403(b)s were created. But back in 1973, in the midst of a terrible bear market, Congress added another option: to put tax-sheltered 403(b) money directly into mutual funds. That isn’t the only way to invest this retirement cash in the stock market. Variable 403(b) annuities allow teachers to invest their contributions in stock funds inside the plans. But here’s what bugs MacLaren. Those annuities almost always come with extra fees—mortality and expense charges—that can eat up 1.3% or so of the account value each year. Well-known fund companies may be found inside the annuity, but the funds are not necessarily the same as the ones they offer outside the annuity. And if you want to switch your investment, you could be nailed with surrender charges. We say extra fees are “almost always” a drawback to annuities because the plan MacLaren uses for his own retirement stash is an exception. His money is in a stock fund inside a tax-deferred annuity offered by TlAA-CREF, the huge retirement plan open to all employees of colleges, universities, private schools and nonprofit educational organizations. Fund expenses are far below average and returns aren’t nicked by mortality fees. So what’s MacLaren’s beef? Public school teachers such as his wife, Phyllis, can’t join TIAA-CREF. When she taught art at a school in Rio Rancho, N.M. (where the couple lived briefly after Grant took early retirement in 1993), she was offered 18 investment choices for her 403(b). Every one was an annuity with fees the MacLarens considered a waste of money. The couple tried to persuade the school to add a no-load fund family—Founders, Montgomery, Twentieth Century and Vanguard were among their suggestions—to the menu. When they were turned down, Phyllis decided to pass up the 403(b) tax break rather than be forced into an annuity. She paid tax on the part of her salary that would have gone into the plan and put what was left in Vanguard’s no-load Index Trust 500 fund. That move, at the beginning of 1995, was unbelievably timely. The fund returned more than 37% that year—enough, says Grant, to push Phyllis's after-tax investment ahead of any pretax investment she could have made inside the 403(b). That made the MacLarens true believers. When they returned to the St. Louis area at the end of l995—and Phyl1is’s new school offered 18 403(b) choices but, again, not a single no-load fund family—the couple went back to work. This time, they were successful. The University City school district agreed to add Vanguard to its list of choices if the MacLarens could persuade at least ten teachers to sign up. Armed with hand-outs singing the praises of no-load funds and excoriating the fees attached to annuities, Grant drummed up support at teachers’ meetings. With the backing of some 15 to 20 teachers, Vanguard was added to the plan.

FUNDS FOR YOUR 403(B)? The NEA Valuebuilder is a variable annuity that offers teachers 14 mutual fund options, imposes an insurance charge of 1.3% a year and carries a surrender charge—a back-end load that kicks in if you pull your money out of the annuity before the company has recovered its sales expenses. The charge is 7% the first year, 6% the second and so on until it disappears after seven years. Also look at the management fees of the funds inside the annuity. Valuebuilder, for example, offers a stock fund from Dreyfus that's designed to track Standard 8c Poor’s 500-stock index. Annual management expenses are 0.39%. That seems modest until you compare it with the ultralow 0.20% management fee on Vanguard’s Index 500 fund. By avoiding the insurance charge and the higher management fee inside the annuity, investing directly in Vanguard's fund would save 1.5% a year and make a big difference in your nest egg. Assume you make a contribution of $300 a month for 20 years and the Vanguard fund returns 10% a year (its average return over the past 20 years is slightly above 15%). Because of the extra fees, the 403(b) fund would return just 8.5%. At the end of 20 years, you'd have $215,480 in the no-load fund, compared with $180,840 in the annuity.

CARRYING ON THE BATTLE

There is another way to get 403(b) money into a no-load fund: Contribute to your employer’s plan and then transfer the money to a 4-03(b)(7) custodial account that you set up with a fund. But you have to be careful to avoid surrender charges and watch for restrictions that may be imposed if your plan olfers a match. And you have to arrange the transfers yourself. Most teachers find this more of a hassle than it’s worth, says Marda Haas, a marketing manager at Vanguard who handles 403(b) accounts. She reports that Vanguard has only a handful of such accounts. One caveat: If you move from an annuity to a direct fund investment, you give up a bit of insurance: the promise that if you die, your beneficiary will get at least as much as you have contributed, even if investment losses mean your account is worth less. Many teachers are apparently concluding that such a promise isn't worth the price. Wendland, who sells the NEA annuity, says that teachers are telling him they don't want to have to pay the insurance cost for the annuity. NEA’s response? It's working to develop a direct fund investment plan to offer as a 403(b) alternative. It should be launched within the coming year.

Reporter: Stacy Stover

The above article appeared in Kiplinger’s Personal Finance Magazine, September, 1997. To see the cover of that issue and the pages containing the article, click on their thumbnails:

A word of advice: One of the very first to bring the shortcomings of the TSA (Tax Sheltered Annuity) to the fore was Steve Schullo of the Los Angeles Unified School District. If you are a teacher (or anyone else eligible for a 430b) I urge you to meet Steve and his partner Dan Robertosn on their excellent blog www.latebloomerwealth.com. -=Grant=-

A friend asked about the “yellow car” photo. My reply:

PS -- The yellow car was not the one Terry and I were supporting, but was my favorite of all the cars in the race, and I had become good friends with its owner, so I asked him if we could use it for a “prop.”

Ads are selected by Google: Another pretty good web page by Grant MacLaren

|